ORTHODOXY and HESYCHASM: The Jesus Prayer, Prayer of the Heart, and Inner Stillness in Eastern Orthodoxy

Hesychasm as the Living Heart of Orthodox Christianity

Hesychasm is not a side tradition within Orthodoxy. It is not an optional spiritual specialty reserved for monks or mystics. Hesychasm is the inner life of Orthodox Christianity itself. It is the Church’s ancient path of repentance, watchfulness, and continual prayer, handed down from the deserts of Egypt through Byzantium, preserved on Mount Athos, and quietly lived today by countless Orthodox Christians around the world.

At its core, Hesychasm is the practice of learning how to stand before God with awareness.

It is the gradual gathering of the scattered human person back into unity through prayer. It is the healing of the heart through repentance. It is the slow transformation of the mind through watchfulness. It is the steady remembrance of Jesus Christ until prayer becomes woven into consciousness itself.

Orthodoxy has always understood that salvation is not merely legal forgiveness or intellectual belief. Salvation is healing. It is restoration. It is participation in divine life. Hesychasm exists for this purpose. Through inner stillness and the Jesus Prayer, the Orthodox Christian learns to cooperate with grace so that the entire person, mind, heart, body, and will, becomes oriented toward Christ.

This page exists to serve as a comprehensive Orthodox guide to Hesychasm.

It is written for seekers who are encountering this tradition for the first time. It is written for catechumens and converts who want to understand how inner prayer fits within Orthodox life. It is written for lifelong Orthodox faithful who feel drawn toward deeper stillness but may not yet have language for what they are experiencing. And it is written for anyone who senses that modern life has fragmented the soul and is searching for a path back to interior wholeness.

Hesychasm matters today because the conditions it addresses have only intensified.

Modern life is saturated with noise, speed, and distraction. The mind is constantly pulled outward by screens, obligations, anxieties, and endless information. Even when the body rests, the inner world often remains restless. Thoughts race. Emotions fluctuate. Attention scatters. Many people live with a persistent sense of spiritual disconnection without fully understanding why.

Orthodox Hesychasm speaks directly to this condition.

It teaches that the primary struggle of the human person is interior. It teaches that thoughts shape the soul. It teaches that prayer is not merely something we do occasionally, but something we are called to become. Through the Jesus Prayer and watchfulness, Hesychasm offers a way for the heart to return to God again and again in the midst of ordinary life.

Importantly, Hesychasm is not escapism. It does not ask believers to withdraw from responsibility, relationships, or reality. Instead, it teaches how to carry inner stillness into work, family life, suffering, and service. The Hesychast learns to remain attentive to God while fully present to the world. Prayer accompanies walking, driving, labor, conversation, and rest. The outer circumstances may remain busy, but the inner orientation changes.

Over time, this inward reorientation reshapes everything.

Anxiety softens. Reactive emotions lose their grip. Compassion deepens. The heart becomes more receptive to grace. Prayer begins to arise spontaneously, even without conscious effort. This is what the Orthodox tradition calls prayer of the heart, a state in which remembrance of God becomes continuous.

Throughout this guide, you will explore Hesychasm from its earliest roots among the Desert Fathers and Mothers, through its development in Byzantine monasticism, its preservation on Mount Athos, and its theological articulation by Saint Gregory Palamas. You will learn how the Jesus Prayer emerged, how watchfulness works, what the Philokalia teaches, and how Hesychasm is practiced today by both monks and laypeople. You will also see how this ancient path continues quietly in modern Orthodox life, carried in the hearts of ordinary believers who are learning to pray unceasingly.

This is not presented as theory.

Hesychasm has always been transmitted through lived experience. It is learned through practice, patience, repentance, and humility. It unfolds slowly, often invisibly, reshaping the soul beneath the surface long before outward changes appear.

The goal of this page is not simply to inform you.

It is to help you understand what Orthodox Christianity has always known: that God desires to be encountered personally, that prayer can become continuous, and that the human heart can become a dwelling place of divine grace.

Hesychasm is the Church’s quiet answer to fragmentation. It is Orthodoxy’s inner medicine for the soul. And it remains, now as always, the living heart of Orthodox Christianity.

What Is Hesychasm in Orthodox Christianity?

In Orthodox Christianity, Hesychasm is not a spiritual hobby, a specialized discipline for monks, or an advanced mystical option for particularly religious people. Hesychasm is Christianity lived inwardly. It is the Church’s ancient way of teaching the human person how to return to God with the whole of their being.

At its most basic level, Hesychasm refers to a life of inner stillness rooted in continual prayer, repentance, and watchfulness. But this definition only scratches the surface. Hesychasm is not merely a prayer practice. It is a complete spiritual orientation. It shapes how the Orthodox Christian thinks, prays, struggles, repents, and gradually becomes transformed by grace.

The word Hesychasm comes from the Greek hesychia, which means stillness, silence, quiet, or rest. In Orthodox spiritual language, this does not mean external silence alone. It refers to an interior condition: a mind that has learned to settle, a heart that has become attentive, and a soul that is learning how to remain present before God.

This inner stillness is not emptiness. It is awareness.

Hesychia describes the state in which the scattered human person begins to gather inwardly. Thoughts slow. Emotional turbulence softens. Attention moves from constant outward distraction toward inward remembrance of God. The heart becomes the center of spiritual perception, and prayer gradually becomes the background rhythm of life.

This is why Hesychasm cannot be separated from lived Orthodoxy.

Orthodox Christianity has never understood faith as merely intellectual agreement with doctrines. Nor has it viewed salvation as simply moral improvement. From the beginning, the Church has taught that salvation is healing and transformation. Humanity is wounded by sin, distraction, fear, and disordered desire. The image of God within us is obscured, not destroyed, and it must be restored through repentance and grace.

Hesychasm exists precisely for this restoration.

Through continual prayer and watchfulness, the Hesychast learns to cooperate with God in the healing of the inner world. The mind is purified from obsessive thoughts. The heart is softened from resentment and hardness. The will is gradually aligned with divine love. This process unfolds slowly, but it is deeply real.

In Orthodoxy, salvation is not understood primarily as a legal declaration. It is understood as participation in divine life.

This participation is called theosis.

Theosis means becoming united with God through grace, not by nature, but by communion. It does not mean becoming God. It means sharing in God’s life, God’s light, and God’s love. It is the gradual transformation of the human person so that Christ lives within them.

Hesychasm is one of the Church’s primary paths toward this union.

Through the Jesus Prayer, the believer continually places themselves before Christ. Through watchfulness, they learn to recognize and release destructive thoughts before they take root. Through repentance, they remain honest about their weakness. Through humility, they open themselves to grace. Over time, these simple practices reshape the soul.

The Orthodox tradition teaches that the human person is not divided into separate spiritual and physical compartments. We are unified beings. The mind, heart, body, and will are meant to work together in harmony. Sin fractures this unity. Hesychasm restores it.

This is why Hesychasm is often described as healing the whole person.

It does not address symptoms alone. It works at the root. It teaches the mind how to be attentive. It teaches the heart how to soften. It teaches the body how to participate through posture, breathing, and stillness. It teaches the will how to return again and again to God.

Over time, the person becomes less reactive and more present. Anxiety loosens its grip. Old emotional patterns weaken. Compassion grows. Prayer becomes less effortful and more natural. What begins as intentional repetition gradually becomes spontaneous remembrance.

This is not mystical fantasy. It is the slow, steady work of grace in a soul that remains faithful.

Hesychasm is therefore not about escaping the world or withdrawing from responsibility. It teaches how to remain inwardly still while fully engaged in life. The Orthodox Christian learns to carry prayer into work, relationships, suffering, and service. Inner stillness becomes portable. God is encountered not only in church or solitude, but in ordinary moments throughout the day.

Seen this way, Hesychasm is not an optional spirituality layered on top of Orthodoxy. It is Orthodoxy’s inner dimension. It is how doctrine becomes experience. It is how repentance becomes transformation. It is how prayer becomes life.

Hesychasm teaches that Christianity is not merely something we believe.

It is something we become.

Hesychia: Inner Stillness and the Gathering of the Heart

To understand Hesychasm, one must understand what Orthodoxy means by the heart.

In modern language, the heart is usually associated with emotion. In Orthodox spiritual anthropology, the heart is something far deeper. It is the center of the human person. It is where thought, desire, memory, conscience, and intention converge. The heart is the inner sanctuary of the soul. Scripture speaks of it this way repeatedly, not as sentiment, but as the place where a person truly lives.

When Orthodox writers speak about prayer entering the heart, they are not speaking poetically. They mean that awareness of God moves from the surface level of mental activity into the deepest interior center of the person.

This matters because most people do not live from the heart.

They live from fragmentation.

The modern soul is scattered. Attention is constantly pulled in competing directions. The mind jumps from memory to worry, from desire to resentment, from fantasy to planning. Even in moments of physical stillness, the interior world often remains restless. Thoughts multiply. Emotions fluctuate. Identity becomes tied to noise and stimulation. Over time, this constant dispersion weakens spiritual awareness and leaves many people feeling disconnected from themselves, from others, and from God.

Orthodox Hesychasm recognizes this fragmentation as one of humanity’s deepest wounds.

Sin does not merely involve immoral actions. It fractures interior unity. The mind becomes detached from the heart. Desire becomes disordered. Attention becomes scattered. The person lives outwardly, reactive to circumstances, driven by impulses and emotional patterns rather than anchored in divine presence.

Hesychia addresses this condition at its root.

Hesychia is not passivity. It is recollection.

It is the gradual gathering of the dispersed mind back into the heart. This process is sometimes called the “descent of the mind into the heart.” It does not mean suppressing thoughts or forcing silence. It means gently redirecting attention again and again toward God through prayer.

At first, this feels artificial. The mind wanders constantly. Prayer feels mechanical. Stillness seems impossible. But Hesychasm does not demand perfection. It teaches return.

Each time attention drifts, the practitioner returns to the Jesus Prayer. Each return is an act of love. Each return slowly retrains the soul. Over time, the mind begins to settle. The heart becomes more sensitive. Interior awareness deepens. What was once scattered begins to cohere.

This is recollection.

Not recollection as memory, but recollection as reintegration.

The person begins to live from a deeper place.

Stillness in Hesychasm is often misunderstood as emptiness or blankness. In reality, it is the opposite. Hesychastic stillness is full. It is attentive presence. It is the quiet awareness of standing before God. It is listening rather than analyzing. It is receptivity rather than control.

The Hesychast does not seek to erase thought. Thoughts still arise. Emotions still appear. Life continues. What changes is relationship to them. Instead of being carried away by every inner movement, the person learns to observe and gently return to prayer. Stillness becomes the space in which God is consciously remembered.

This is why Orthodoxy emphasizes interior silence.

Not because silence itself is holy, but because silence creates the conditions for communion.

Noise keeps the soul outward. Silence allows the heart to turn inward. In silence, hidden fears surface. Old wounds become visible. Compulsive thoughts reveal themselves. This can be uncomfortable, which is why many avoid stillness. But Hesychasm teaches that this exposure is necessary for healing. What is brought into awareness can be offered to God. What remains buried continues to govern unconsciously.

Interior silence allows grace to work.

It gives space for repentance to arise naturally. It makes room for humility. It softens resistance. Over time, it restores intimacy with God. The person begins to sense divine presence not as an idea, but as a quiet reality within.

This is the heart of Hesychia.

It is not withdrawal from life. It is learning how to live from the inside out.

Through inner stillness, the Orthodox Christian discovers that God is not distant or abstract. He is encountered in the depths of the heart. And as the mind learns to dwell there, prayer becomes less effortful, awareness becomes more stable, and life begins to reorganize itself around presence rather than distraction.

Hesychia is not something achieved.

It is something received.

It unfolds slowly as the soul learns to remain still before God, allowing Him to gather together what has been scattered, and to restore the human person to wholeness.

The Jesus Prayer: Center of Orthodox Hesychasm

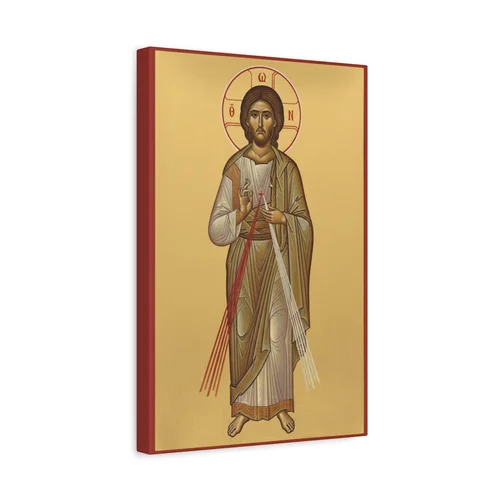

At the center of Orthodox Hesychasm stands a single prayer that carries the weight of the entire spiritual tradition:

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

This prayer is not a devotional accessory. It is the living heart of Hesychastic practice. Everything in Hesychasm flows toward it, and everything flows from it.

The Jesus Prayer is not treated in Orthodoxy as a mantra, affirmation, or relaxation technique. It is a direct invocation of a living Person. To speak the name of Jesus is to turn consciously toward Him. The prayer places the one who prays in immediate relationship with Christ, acknowledging His divinity, confessing personal brokenness, and appealing to divine mercy all at once.

Within this single sentence, the whole Gospel is present.

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God” proclaims who Jesus truly is. “Have mercy on me” expresses humanity’s continual dependence on grace. “A sinner” is not self-hatred but spiritual honesty, a refusal to pretend wholeness where healing is still needed. The prayer is simple, but it is uncompromisingly truthful.

Its roots are unmistakably biblical.

Throughout the Gospels, people approach Christ with short, direct cries for mercy. The blind man Bartimaeus calls out, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me.” The tax collector in Christ’s parable stands at a distance and prays, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner.” These prayers are not polished or elaborate. They are raw appeals born from humility and faith.

The Jesus Prayer gathers these Scriptural cries into one continuous invocation.

It also answers a command that Orthodox Christianity has always taken literally. Apostle Paul instructs believers to “pray without ceasing.” This was never understood as poetic exaggeration. The early Church recognized it as a real spiritual calling. Prayer was meant to become continuous, not confined to set moments or formal services.

This raised a practical question that shaped the entire Hesychastic tradition: how does a person pray continually while still living an ordinary life?

The answer emerged gradually through experience. Short prayers could be repeated throughout the day. Long prayers could not. Brief invocations such as “Lord, have mercy,” “God, help me,” or simply the holy name of Jesus allowed prayer to accompany walking, working, traveling, and resting.

Over time, the invocation of Jesus’ name took on special importance. Orthodox Christians understood that Christ’s name is not merely a label. It carries presence. To call upon Jesus is to place oneself before Him in awareness and humility. The prayer becomes a meeting place between human weakness and divine mercy.

As monastic life developed, especially in the desert communities of Egypt and Palestine, this practice deepened. The Desert Fathers discovered that repetition of the Jesus Prayer was not about producing spiritual feelings. It was about recollection. Each return to the prayer gathered the scattered mind. Each invocation redirected attention away from intrusive thoughts and back toward God. Slowly, the prayer began to move inward.

What started as spoken words became interior awareness.

This is what Orthodox tradition calls prayer of the heart.

Prayer of the heart does not mean emotional intensity or mystical excitement. It means that remembrance of God has taken root at the center of the person. The prayer is no longer something performed occasionally. It becomes a quiet background presence, continuing even when the person is not consciously repeating it.

At first, the Jesus Prayer feels deliberate. You choose to say it. You forget it. You remember again. The mind wanders constantly. This is normal. Hesychasm does not demand perfection. It teaches return. Each return to the prayer is already prayer.

Over time, with faithful repetition, something subtle begins to happen. The words feel less external. The invocation starts to arise spontaneously. The prayer accompanies ordinary activities. Some practitioners eventually become aware of the prayer continuing softly within them while working, driving, or speaking with others.

This is not achievement. It is grace received through perseverance.

The Orthodox Church has always warned that this process must be grounded in humility. The Jesus Prayer is not used to chase experiences, visions, or spiritual sensations. In fact, Hesychastic teachers consistently caution against seeking such things. Extraordinary experiences are treated with suspicion, because they easily become sources of pride or self-deception.

The true fruits of the Jesus Prayer are quiet and unmistakable.

Increased patience. Softened reactions. Growing compassion. Freedom from compulsive thoughts. Deeper repentance paired with peace. A steady awareness of God’s nearness. Love that becomes more natural and less forced.

This is how the prayer transforms the soul.

The Jesus Prayer also reveals something essential about Orthodox spirituality: salvation is not merely legal forgiveness. It is healing. The prayer gradually restores interior unity. The mind descends into the heart. The heart becomes attentive. The person begins to live from a deeper place. Fragmentation gives way to coherence. Anxiety loosens its grip. Inner noise subsides.

The prayer does not remove struggles from life.

It changes how life is carried.

Through the Jesus Prayer, Hesychasm fulfills the apostolic command to pray without ceasing, not by constant verbal effort, but by transforming the inner orientation of the soul. Prayer becomes woven into consciousness itself. Communion with Christ becomes continuous rather than occasional.

This is why the Jesus Prayer stands at the center of Orthodox Hesychasm.

It is not a technique.

It is relationship.

It is the steady turning of the whole person toward Christ, repeated patiently until remembrance of God becomes as natural as breathing.

And in that quiet persistence, the heart learns to remain before Him.

Biblical Roots of the Jesus Prayer

The Jesus Prayer did not emerge in isolation, nor was it invented by monks seeking mystical techniques. It arose organically from Scripture itself and from the earliest Christian struggle to live in continual awareness of God. Long before Hesychasm was named, the spiritual logic behind it was already woven throughout the Bible.

One of the clearest foundations appears in the healing of the blind man near Jericho. As Christ passes by, the man cries out repeatedly, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me.” He does not offer a long theological explanation. He does not construct a formal prayer. He simply calls upon Jesus by name and begs for mercy with persistence and faith. The crowd attempts to silence him, yet he cries out even louder. Christ stops, responds, and heals him.

Orthodox tradition has always seen this moment as more than a miracle story. It reveals something essential about prayer itself. The blind man teaches that authentic prayer is direct, humble, persistent, and personal. He calls upon Christ. He confesses his need. He refuses distraction. These same elements form the heart of the Jesus Prayer.

Another foundational image comes from Christ’s parable of the tax collector and the Pharisee. While the Pharisee lists his virtues, the tax collector stands at a distance, unable even to lift his eyes toward heaven, and prays simply, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner.” Christ declares that this man, not the Pharisee, goes home justified.

This short prayer becomes one of the deepest spiritual templates in Orthodox Christianity. It embodies repentance without despair and humility without self-loathing. The tax collector does not analyze his sins or attempt spiritual performance. He places himself honestly before God and asks for mercy. The Jesus Prayer preserves this posture exactly. It teaches the soul to stand naked before God, not hiding weakness, not defending ego, and not pretending righteousness.

These Gospel moments establish the pattern: prayer rooted in humility, focused on Christ, and sustained through perseverance.

The apostolic foundation deepens this understanding even further. Apostle Paul commands believers to “pray without ceasing.” He repeats this theme elsewhere when urging Christians to pray at all times and remain spiritually watchful. These were not rhetorical flourishes. The early Church received them as literal spiritual instructions.

This immediately raised a practical question for the first Christians. How does one pray continually while working, traveling, raising families, and surviving daily life?

The solution emerged through lived experience rather than abstract theology. Long spoken prayers were difficult to sustain throughout the day, but short invocations could accompany every activity. Early Christians began repeating brief prayers such as “Lord, have mercy,” “God, help me,” or simply the name of Jesus. These phrases allowed prayer to flow through ordinary moments rather than being confined to formal worship.

Over time, the invocation of Jesus’ name became central. The Church understood that Christ’s name is not merely symbolic. To call upon Jesus is to place oneself consciously in His presence. The repetition of His name was not treated as magic or formula, but as relationship. Each invocation became a turning of the heart toward Christ.

This is how continuous prayer began to take shape in early Christianity. Prayer was no longer limited to specific hours. It became something carried internally throughout the day. Work and prayer were no longer separate. Movement and remembrance of God became intertwined.

As monastic life developed in the deserts of Egypt and Palestine, this practice deepened further. The Desert Fathers discovered that short prayers could gather the wandering mind and anchor attention in God. Repetition was not used to escape thoughts but to return from them. Each invocation brought the soul back to Christ. Over time, prayer began to move inward, descending from the lips into the heart.

What Hesychasm later articulated in theology had already been lived for centuries in practice.

The Jesus Prayer represents the convergence of all these biblical streams: the blind man’s cry for mercy, the tax collector’s humility, and the apostolic command to pray without ceasing. It preserves the earliest Christian understanding that prayer is not an occasional activity but a continuous orientation of the soul.

Orthodox Christianity therefore does not treat the Jesus Prayer as one devotion among many. It is the distilled expression of Scripture lived through the heart. It teaches that prayer is not primarily about saying many words, achieving special experiences, or mastering techniques. It is about standing before Christ again and again with honesty, humility, and trust.

From the very beginning, Christianity understood that salvation unfolds through communion, and communion is sustained through prayer.

The Jesus Prayer simply gives this ancient truth a form that can be carried into every moment of life.

Development of the Jesus Prayer in Orthodox Tradition

The Jesus Prayer did not appear fully formed at a single moment in history. Its development unfolded slowly across centuries as Orthodox Christians searched for practical ways to fulfill Christ’s call to constant prayer. What eventually became the familiar invocation, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner,” emerged organically from lived spiritual experience rather than formal theological construction.

In the earliest monastic communities of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, prayer was woven into every aspect of daily life. The Desert Fathers and Mothers discovered quickly that long spoken prayers, while essential in communal worship, were difficult to maintain continuously throughout manual labor, fasting, solitude, and daily survival. As a result, they began using short prayers that could be repeated inwardly at any moment.

These early invocations were simple. “Lord, have mercy.” “God, help me.” “Jesus.” The goal was not poetic beauty or theological completeness. The goal was remembrance of God.

Over time, these brief prayers became spiritual anchors. When thoughts wandered, the monk returned to the prayer. When temptation arose, the prayer was invoked. When fear surfaced, the prayer steadied the heart. Repetition was not mechanical. It was relational. Each return to prayer was a renewed turning toward Christ.

As this practice deepened, something important became clear: invoking the name of Jesus carried unique spiritual weight. Orthodox Christianity has always understood the name of Jesus as inseparable from His Person. To call upon His name is not symbolic. It is participatory. The early ascetics experienced this directly. The name of Jesus gathered the mind more powerfully than abstract prayer. It softened the heart. It brought awareness of Christ’s presence.

This insight gradually shaped the prayer’s development.

By the fourth and fifth centuries, the invocation of Jesus’ name had become central to inner prayer. Monks discovered that repeating Christ’s name with attention created interior stability and clarity. The prayer began to move beyond isolated phrases toward a fuller confession of faith. Jesus was not only invoked as helper or healer but explicitly acknowledged as Lord and Son of God.

At the same time, the humility of the tax collector’s prayer, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner,” was being preserved. Orthodox spirituality never separated prayer from repentance. The heart of prayer was not self-improvement or spiritual experience but standing honestly before God in need of mercy.

Gradually, these elements converged.

Christ’s name. His divine identity. The confession of personal sinfulness. The appeal to mercy.

What emerged was not a formula imposed from above, but a prayer shaped from below, refined through centuries of ascetic struggle and spiritual discernment. By the time Hesychasm was formally articulated in Byzantine theology, the Jesus Prayer was already deeply embedded in Orthodox monastic life.

Its final form held everything essential in a single breath.

Lord Jesus Christ affirms relationship and surrender. Son of God proclaims divine truth. Have mercy on me acknowledges dependence on grace. A sinner preserves humility.

This structure ensured that prayer remained both doctrinally sound and spiritually grounded. The prayer confessed Christ rightly while guarding the soul against pride. It invited intimacy with God while preserving reverence.

Equally important was how the prayer was practiced.

Orthodox tradition never treated the Jesus Prayer as a technique to master. It was always paired with watchfulness, repentance, fasting, confession, and obedience. The prayer was not isolated from the sacramental life of the Church. It existed within it. Divine Liturgy, Scripture, spiritual guidance, and inner prayer formed a unified whole.

The invocation of Jesus’ name became a way of carrying the life of the Church into the interior world.

As the prayer spread from the desert into Byzantine monasteries and eventually throughout the Orthodox world, it retained this balanced character. It was simple enough for beginners and deep enough to occupy saints for a lifetime. It could be prayed quietly by peasants and rigorously by monks. It accompanied walking, working, illness, solitude, and worship.

Most importantly, the Jesus Prayer was never reduced to repetition alone. The Fathers consistently emphasized attention of the heart. Without attentiveness, repetition becomes empty. With attentiveness, even a few words become transformative.

Through centuries of practice, Orthodox Christianity came to understand something profound: the name of Jesus, when invoked with humility and perseverance, gradually reshapes the inner person. It gathers the scattered mind. It softens the hardened heart. It restores unity between thought and prayer.

This is why the Jesus Prayer stands at the center of Orthodox Hesychasm.

Not because it is ancient.

Not because it is traditional.

But because it works.

It quietly accomplishes what every Christian longs for: a heart that remembers God continually.

Why the Jesus Prayer Is Not a Mantra

One of the most common misunderstandings about the Jesus Prayer, especially among modern spiritual seekers, is the assumption that it functions like a mantra. From the outside, repetition can look similar. A phrase is spoken again and again. The breath may be involved. The mind gradually becomes quieter. Because of this surface resemblance, some assume that Hesychasm is simply a Christian version of Eastern meditation techniques.

Orthodox Christianity firmly rejects this idea.

The Jesus Prayer is not a technique designed to alter consciousness. It is not a psychological exercise meant to induce calm. It is not a spiritual hack for accessing special states of awareness. At its core, the Jesus Prayer is personal invocation. It is direct relationship. It is communion.

A mantra works by sound, rhythm, or vibration. Its power lies in repetition itself. The Jesus Prayer works because it addresses Someone.

Every repetition of the prayer is a turning toward Christ. Each invocation is an act of faith. The words are not empty syllables meant to dissolve the ego. They are a confession of who Jesus is and who we are before Him. “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God” proclaims divine identity. “Have mercy on me, a sinner” expresses dependence, humility, and repentance.

This personal dimension changes everything.

In Hesychasm, repetition is never the goal. Relationship is.

The Fathers consistently teach that if repetition becomes mechanical, the prayer loses its spiritual power. The words must be accompanied by attention and sincerity. Even a thousand repetitions mean nothing if the heart is absent. But even a few repetitions, offered with awareness and humility, carry profound spiritual weight.

Orthodox tradition therefore places enormous emphasis on interior attentiveness. The prayer is meant to arise from the heart, not merely pass through the lips. The practitioner is not trying to empty the mind into nothingness. Instead, the mind is gently gathered and offered to Christ. Thoughts are not suppressed through force. They are released through return to relationship.

This is why Hesychasm never separates the Jesus Prayer from repentance.

A mantra aims at detachment from personal identity. The Jesus Prayer deepens personal encounter. A mantra seeks impersonal stillness. The Jesus Prayer leads into communion with a living God. A mantra dissolves distinction. The Jesus Prayer preserves relationship between Creator and creature while drawing them closer together through grace.

The difference is not subtle.

Hesychasm is not about escaping selfhood. It is about healing it.

Prayer does not erase the person. It restores the person.

Another key distinction is intention. In mantra-based systems, repetition itself produces effect. In Orthodox prayer, everything depends on posture of the heart. Pride blocks prayer. Humility opens it. Repentance deepens it. Love sustains it. Without these, repetition becomes empty sound.

This is why Orthodox spiritual writers repeatedly warn against chasing experiences. Peace, warmth, light, or emotional comfort are never the objective. These may arise or they may not. They are treated as secondary and often approached with caution. The true measure of prayer is transformation: increased patience, softened reactions, deeper compassion, freedom from compulsive thoughts, and growing awareness of God’s presence.

The Jesus Prayer is therefore not spiritual automation.

It is ongoing dialogue.

It teaches the soul to remain oriented toward Christ in every circumstance. It invites the heart into continual dependence. It cultivates trust rather than control. Over time, prayer becomes less something we perform and more something we participate in.

This is why Hesychasm insists that prayer is communion.

Each invocation is a meeting.

Each return to the prayer is a return to relationship.

And as that relationship deepens, the inner world slowly reorganizes around love rather than fear.

The Jesus Prayer does not quiet the mind by emptying it.

It quiets the mind by filling it with Christ.

That is the difference.

Prayer of the Heart

Within Orthodox Hesychasm, the Jesus Prayer is not meant to remain only on the lips or in the mind. Its true destination is the heart. The Fathers describe this movement as the “descent of prayer,” a gradual interiorization where prayer passes from deliberate repetition into the deepest center of the human person.

At first, the prayer is spoken intentionally. The believer chooses to say the words. Attention wanders, distractions arise, and effort is required to return again and again to the invocation. This stage is normal and unavoidable. The mind has been trained for years to scatter itself across worries, memories, and desires, so learning to remain present with prayer feels unfamiliar.

Over time, however, something begins to change.

Through steady repetition combined with watchfulness and humility, the prayer starts to take root. The words no longer feel external. Instead of being carried by conscious effort alone, the prayer begins to echo inwardly. The Fathers describe this as prayer moving from the lips into the heart, meaning that remembrance of God becomes centered in the spiritual core of the person rather than remaining only at the surface level of thought.

This descent is not forced. It cannot be manufactured by technique or accelerated by intensity. It happens quietly, often without the person realizing it at first. Many practitioners only recognize the change in hindsight, noticing that prayer has begun to accompany them naturally throughout the day.

Eventually, for those who persevere faithfully, the Jesus Prayer may become automatic.

This does not mean robotic repetition or loss of awareness. It means that the heart itself begins to pray. The invocation continues softly beneath conscious thought, much like breathing or the rhythm of the heartbeat. Even while speaking with others, working, or moving through daily responsibilities, the prayer remains present in the background of awareness.

Thoughts still arise. Conversations still happen. Life continues exactly as before on the outside. Yet inwardly, something has shifted. Prayer is no longer something that must be constantly restarted. It flows quietly on its own.

Orthodox tradition calls this state “prayer of the heart.”

Prayer of the heart is not emotional ecstasy, altered consciousness, or mystical sensation. It is steady interior remembrance of God. The soul becomes oriented toward Christ in a continuous way. Instead of repeatedly pulling the mind back to prayer, the person discovers that prayer is already there, waiting beneath the surface of thought.

Many describe becoming aware of the prayer physically in the chest, not as imagination, but as a gentle interior rhythm. Others experience it simply as a quiet sense of Christ’s nearness. However it manifests, the defining characteristic is not feeling but stability. The heart remains turned toward God even when attention moves outward.

This interior remembrance produces profound changes over time.

Anxiety loses its urgency. Reactive thoughts soften. Emotional turbulence settles more quickly. Compassion grows naturally. The person becomes less driven by impulse and more grounded in presence. Life begins to feel less fragmented because prayer now holds everything together from within.

Importantly, prayer of the heart does not remove struggle from life. Difficult emotions still arise. Temptations still appear. Suffering still exists. The difference is that the soul now meets these realities from a place of inner stillness rather than inner chaos. Prayer becomes a refuge that is always available, not as escape, but as communion.

The Fathers consistently teach that attaining prayer of the heart is one of the most beautiful gifts available to a Christian, not because it feels extraordinary, but because it feels natural. The soul finally rests where it was always meant to rest, in continual awareness of God.

This is not spiritual achievement. It is healing.

The scattered mind is recollected. The divided heart becomes unified. The person begins to live from the inside out rather than being driven by external circumstances. Prayer ceases to be something added onto life and becomes the quiet foundation beneath it.

Hesychasm understands this as the normal fruit of faithful perseverance. It does not belong only to monks or mystics. It is offered to anyone willing to return to Christ again and again with humility and patience.

Prayer of the heart is simply what happens when love becomes continuous.

The Desert Fathers and Mothers: Birthplace of Hesychasm

Hesychasm did not originate in academic theology or organized spiritual programs. Its roots lie in the lived experience of the earliest Christian ascetics who withdrew into the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria during the third and fourth centuries. These men and women, later known collectively as the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers, were not pursuing mystical novelty. They were responding to a radical call of the Gospel to seek God with an undivided heart.

As Christianity became more socially accepted after periods of persecution, some believers felt that comfort and cultural assimilation were dulling spiritual intensity. They left cities and villages behind, not out of rejection of humanity, but out of longing for interior freedom. The desert offered what ordinary life could not: silence, simplicity, and the removal of constant distraction.

Their lives were stark. They owned almost nothing. They ate little. They slept lightly. Their days were structured around prayer, manual labor, and Scripture. Many lived alone in small cells or caves. Others gathered loosely in communities, united by shared rhythms of worship and silence. What they sought was not hardship for its own sake, but clarity of heart.

In the stillness of the desert, something unexpected emerged.

Even when all external noise disappeared, inner noise remained.

Memories surfaced. Old wounds reopened. Desires intensified. Fears became louder. The ascetics discovered that solitude did not automatically bring peace. Instead, it revealed the true condition of the soul. The desert stripped away distractions and exposed the inner world with brutal honesty.

It was here that Christian spirituality underwent a profound deepening.

The early ascetics realized that the primary battlefield was not outside them but within. Thoughts became their central concern. They observed how certain thoughts carried temptation, how others produced anger or despair, and how still others quietly fed pride. They noticed that if a thought was entertained long enough, it would attach itself to emotion, and from emotion it would move toward action.

This was the birth of Orthodox spiritual psychology.

Rather than viewing sin only as outward behavior, the Desert Fathers and Mothers recognized that spiritual struggle begins at the level of attention. A thought enters. If it is welcomed, it grows. If it is gently released through prayer, it fades. Over time, they learned that vigilance over the mind was essential for purity of heart.

This realization gave rise to what later tradition would call watchfulness.

Watchfulness was not rigid self-control. It was attentive presence. The ascetic learned to observe thoughts as they appeared and to return immediately to God rather than becoming entangled in mental narratives. Prayer became the primary tool of this inner warfare. Short invocations were repeated throughout the day to gather the scattered mind and anchor the heart in God.

Silence played a crucial role in this process.

External silence allowed the inner movements of the soul to become visible. Radical simplicity removed unnecessary stimulation. Fasting weakened compulsive desire. Manual labor grounded the body. Scripture provided spiritual orientation. All of these worked together to create an environment where prayer could deepen.

Yet the desert ascetics were not seeking isolation for its own sake. Their goal was transformation.

They wanted hearts free from domination by passions. They wanted minds capable of stillness. They wanted to love God without distraction and love others without condition. Hesychasm emerged naturally from this longing. It was not a technique imposed on life. It was the shape life took when everything unnecessary was stripped away.

Importantly, the Desert Fathers and Mothers did not see themselves as spiritual heroes. Their writings are filled with humility, repentance, and awareness of weakness. They spoke openly about failure, distraction, and temptation. Progress was slow. Setbacks were frequent. Growth happened quietly.

What distinguished them was perseverance.

They returned to prayer again and again. They learned to stand before God without pretense. They accepted that healing unfolds over time. Through this fidelity, they discovered that stillness is not achieved by force but received through patience.

The desert tradition revealed something foundational that Hesychasm still teaches today: you do not overcome inner chaos by controlling it. You overcome it by turning toward God. You do not silence thoughts through aggression. You release them through remembrance of Christ. You do not heal the soul by escaping life. You heal it by learning to remain present before God in every moment.

From these early communities came the essential elements of Hesychasm: continual prayer, watchfulness over thoughts, humility, repentance, and the gradual gathering of the heart. Everything that later developed in Byzantine monasteries and Orthodox theology was already present here in seed form.

The desert was not merely a geographic location.

It was the womb in which Orthodox inner prayer was born.

And its wisdom continues to shape Hesychasm wherever Christians seek stillness of heart today.

From the Desert to Byzantium: How Hesychasm Spread

Hesychasm did not remain confined to the caves and cells of the early desert ascetics. What began in the solitude of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria gradually moved outward through the living networks of Orthodox monasticism, carried not by institutions or programs but by people whose lives had been reshaped by prayer. The tradition spread quietly through relationships, passed from elder to disciple, heart to heart, generation after generation.

This transmission was deeply personal. Hesychasm was never taught primarily through lectures or written manuals. It was learned through proximity and shared life. A younger monk would live alongside an elder, observing how he prayed, how he responded to intrusive thoughts, how he practiced silence, how he repented, and how he treated others. Instruction was often minimal and indirect. Example was everything. The elder did not simply teach prayer; he embodied it, and the disciple absorbed it through daily experience.

This relational model became one of the defining characteristics of Orthodox spirituality. Spiritual knowledge was not treated as abstract information to be acquired, but as wisdom formed through lived struggle. The disciple learned Hesychasm in the same way a child learns language, not through formal explanation but through immersion. Prayer, watchfulness, humility, and repentance were transmitted through shared rhythms of life rather than structured curricula.

As monastic communities expanded, this way of life moved naturally into established centers of Orthodox Christianity. Early desert wisdom found stable expression in monasteries throughout Sinai and Palestine, where silence, fasting, manual labor, and continual prayer were preserved within communal settings. These monasteries became bridges between the radical solitude of the desert and the wider Church, safeguarding the inner tradition while making it accessible to larger communities.

From there, Hesychastic spirituality gradually entered the Byzantine world, including Constantinople and surrounding monastic regions. Here it encountered theology, liturgy, and imperial culture, yet it was not absorbed into abstraction. Monastic communities continued to guard the experiential core of prayer, ensuring that inner stillness remained central even as Orthodox theology became increasingly sophisticated. The movement from desert to city did not dilute Hesychasm. Instead, it revealed its adaptability. The outward environment changed, but the inner orientation remained the same.

What is remarkable is how little Hesychasm actually transformed as it traveled across geography. The same short prayers were used. The same emphasis on watchfulness over thoughts remained. The same insistence on humility and repentance shaped spiritual life. The same cautions against pride and spiritual delusion were repeated. Whether in remote caves or urban monasteries, the essential elements persisted unchanged.

This continuity reveals something fundamental about Hesychasm. It was never tied to a particular place or historical moment. It belonged to the heart. Wherever Orthodox Christians committed themselves to inner prayer, Hesychasm appeared. Wherever elders guided disciples in attentiveness and humility, Hesychasm took root. Wherever believers learned to return again and again to Christ through the Jesus Prayer, Hesychasm lived.

Written texts eventually emerged to preserve this wisdom, but they always followed lived experience rather than preceding it. Teachings were recorded only after they had been embodied. Collections like the Philokalia gathered voices from across centuries, but the tradition itself had already been flowing uninterrupted through personal transmission long before it was compiled into books.

The elder-disciple relationship ensured that Hesychasm remained grounded in reality rather than drifting into theory. Spiritual authority was earned through prayer, not credentials. Guidance came from those who had struggled inwardly, not from those who merely studied spirituality. This living chain of formation allowed Hesychasm to survive political upheaval, cultural change, and theological controversy without losing its core.

Even today, this same pattern continues. Orthodox Hesychasm is still passed primarily through relationship. Spiritual fathers and mothers guide others not by presenting systems but by sharing life. They teach how to notice thoughts, how to return gently to prayer, how to endure dryness, how to repent without despair, and how to remain faithful over long periods of time.

This is how Hesychasm moved from desert solitude into Byzantine monasteries and beyond. It did not spread through structures. It spread through people whose hearts had learned stillness. It continues in exactly the same way, quietly carried by ordinary lives shaped by continual remembrance of God.

Mount Athos: The Spiritual Center of Orthodox Hesychasm

As Hesychasm moved from the deserts of Egypt and Palestine into the Byzantine world, it eventually found its most enduring home on Mount Athos, often called the Holy Mountain. Located on a rugged peninsula in northern Greece, Athos became far more than a collection of monasteries. Over time, it emerged as the spiritual engine of Orthodox Hesychasm, preserving the inner tradition of prayer with extraordinary fidelity for more than a thousand years.

The monastic presence on Athos began in earnest during the ninth and tenth centuries, when hermits and small communities sought refuge in its remote forests and cliffs. The peninsula’s isolation provided ideal conditions for silence, prayer, and ascetic struggle. These early ascetics were heirs to the desert tradition, carrying with them the same emphasis on simplicity, continual prayer, and vigilance over thoughts that had shaped spiritual life in Egypt and Palestine.

A decisive moment came in 963 with the founding of the Great Lavra by Athanasius of Athos, whose vision helped organize Athonite monasticism into a more stable communal structure. Supported by Byzantine emperors, Athos gradually developed into a unique monastic republic, governed not by secular authorities but by its own spiritual leadership. This autonomous structure allowed Athos to remain remarkably insulated from political pressures, enabling generations of monks to devote themselves almost entirely to prayer.

What made Athos unique was not merely its architecture or imperial patronage, but its uncompromising spiritual focus. From its earliest centuries, life on the Holy Mountain revolved around Divine Liturgy, Scripture, fasting, manual labor, and inner prayer. The Jesus Prayer was not treated as a private devotion reserved for mystics but as a living practice woven into the daily rhythm of monastic life. Silence was cultivated intentionally, not as an escape from community, but as a means of deepening communion with God.

Over time, Athos became a gathering place for monks from across the Orthodox world. Greeks, Slavs, Georgians, Romanians, and others brought their cultural traditions with them, yet the inner spiritual orientation remained unified. Regardless of language or nationality, Athonite monasticism preserved the same Hesychastic foundations: humility, repentance, watchfulness, and continual invocation of Christ’s name.

It was on Athos that Hesychasm was refined, safeguarded, and transmitted with exceptional continuity. Spiritual elders guided disciples through lived example rather than formal instruction, teaching them how to recognize intrusive thoughts, how to return gently to prayer, and how to endure inner dryness without abandoning perseverance. The elder-disciple relationship flourished here, ensuring that Hesychasm remained experiential rather than theoretical.

During the fourteenth century, Athos became the epicenter of the Hesychast controversy, when inner prayer was challenged by critics who denied the possibility of real experiential communion with God. Athonite monks stood firmly in defense of their lived tradition, and their spiritual understanding was articulated theologically by Gregory Palamas. The eventual affirmation of Palamas’ teaching by Church councils confirmed what Athonite monks had known through prayer: that God truly shares Himself through His uncreated energies, and that Hesychastic prayer opens the heart to genuine divine communion.

This moment solidified Mount Athos as the spiritual guardian of Orthodox inner life. From that point forward, Athos was widely recognized as the primary stronghold of Hesychasm, a place where the ancient desert tradition continued uninterrupted. While political empires rose and fell around it, Athos remained devoted to the same quiet work of interior transformation.

Across centuries, Athonite monks preserved countless spiritual writings, copying manuscripts by hand and safeguarding texts that might otherwise have been lost. Many of the works later compiled in the Philokalia were transmitted through Athonite communities, making the Holy Mountain instrumental not only in living Hesychasm but also in preserving its literary heritage.

Even today, Athos continues to function as a living monastery rather than a historical monument. Twenty ruling monasteries and numerous sketes and hermitages maintain the same basic rhythm of life established centuries ago. Monks rise before dawn for prayer, participate in long liturgical services, work with their hands, and return continually to inner stillness through the Jesus Prayer. The outward forms may vary slightly between communities, but the interior aim remains unchanged.

What distinguishes Mount Athos is not perfection, but perseverance. Hesychasm has survived here because it has been practiced daily by ordinary men who commit themselves to repentance, silence, and prayer. Athos demonstrates that inner stillness is not achieved through ideal conditions but through faithful repetition of simple acts over long periods of time.

For Orthodox Christianity, Mount Athos stands as living proof that Hesychasm is not a relic of the past. It is a present reality, sustained by continuous prayer and humble obedience. The Holy Mountain remains a spiritual lighthouse, quietly radiating the same message first discovered in the desert: that transformation comes through stillness, communion through humility, and healing through remembrance of Christ.

Major Athonite Hesychasts

Saint Athanasius the Athonite

Saint Gregory of Sinai

Saint Gregory Palamas

Saint Silouan the Athonite

Saint Sophrony of Essex

Saint Paisios of Mount Athos

Saint Porphyrios of Kavsokalyvia

Saint Joseph the Hesychast

The Philokalia: Core Text of Orthodox Hesychasm

No collection of writings has shaped Orthodox Hesychasm more deeply than the Philokalia. Rather than functioning as a single authored work, the Philokalia is a vast spiritual anthology that gathers together voices from across more than a millennium of Orthodox prayer and ascetic experience. Its title comes from two Greek words meaning “love of the beautiful” or “love of the good,” referring not to aesthetic beauty but to the soul’s attraction toward divine life.

The Philokalia spans writings from roughly the fourth century through the fifteenth, preserving the teachings of desert ascetics, Byzantine monks, theologians, and spiritual elders who lived the Hesychastic path firsthand. These texts were not written as abstract theology. They emerged from lives shaped by silence, fasting, prayer, repentance, and interior struggle. Each author speaks from experience rather than theory.

Among its contributors are figures such as Evagrius Ponticus, whose insights into thoughts and inner warfare laid early foundations for Hesychastic psychology, Maximus the Confessor, who articulated the healing of the human will through grace, and Isaac the Syrian, whose writings emphasize compassion, humility, and the gentle work of God within the heart. Later authors include Symeon the New Theologian and Gregory of Sinai, both of whom helped systematize inner prayer while warning against spiritual pride and illusion.

Despite their differences in era and personality, these writers speak with remarkable unity. They consistently return to the same core themes: repentance as the foundation of prayer, humility as its safeguard, watchfulness as its discipline, and love as its fruit.

Repentance in the Philokalia is not treated as emotional guilt or self-condemnation. It is understood as continual turning of the heart toward God, an ongoing reorientation of the soul away from distraction and back toward communion. Prayer without repentance, the Fathers insist, becomes hollow. Inner stillness without humility becomes dangerous. Every Hesychastic practice is therefore grounded in honest self-awareness and dependence on mercy.

Humility occupies a central place throughout the collection. The writers repeatedly warn that spiritual progress is easily distorted by pride. They caution against comparing oneself to others, seeking recognition, or interpreting spiritual feelings as signs of holiness. True prayer, they teach, produces softness of heart rather than spiritual confidence. A person advancing in Hesychasm becomes more aware of weakness, not less.

Watchfulness is presented as the daily labor of the Hesychast. The Philokalia describes in detail how thoughts arise, how they attempt to attach themselves emotionally, and how they gradually shape behavior if left unchecked. The Fathers teach that freedom begins with attention. By noticing thoughts at their first appearance and returning immediately to prayer, the soul learns discernment. This is not suppression but redirection. The mind is gently gathered back into remembrance of God.

One of the most striking features of the Philokalia is its consistent suspicion of extraordinary spiritual experiences. Visions, lights, emotional warmth, or inner sensations are never treated as goals. In fact, they are approached with great caution. The Fathers warn that such experiences can easily become sources of self-deception or pride. They emphasize that authentic Hesychasm unfolds quietly and invisibly, often without any dramatic interior events.

The true measure of spiritual growth, according to the Philokalia, is not mystical experience but transformation of character.

Greater patience. Reduced reactivity. Increased compassion. Freedom from compulsive thoughts. A heart that forgives more easily. A growing awareness of God’s presence in ordinary life.

These are the signs the Fathers consistently point to.

Above all, the Philokalia insists that love is the ultimate criterion of Hesychasm. Prayer that does not lead to love for others is incomplete. Stillness that does not overflow into mercy is false. Inner peace that remains self-contained has missed its purpose. Every Hesychastic practice is meant to soften the heart toward God and toward people.

The collection also makes clear that Hesychasm is not reserved for spiritual elites. While many of the writings emerged from monastic contexts, their guidance is deeply practical and human. The Fathers speak openly about distraction, discouragement, boredom, and failure. They acknowledge how slowly progress comes and how often one must begin again. Their tone is realistic rather than idealized.

The Philokalia does not present Hesychasm as a technique to master but as a lifelong process of healing. It assumes that prayer matures over decades, not weeks. It teaches patience with oneself. It honors small acts of faithfulness. It understands that God works gradually, reshaping the soul layer by layer.

For Orthodox Christianity, the Philokalia stands as both a spiritual map and a mirror. It offers guidance for the journey inward while reflecting back the condition of the heart. It preserves the living voice of Hesychasm across centuries, reminding every generation that inner stillness is not achieved through intensity, but through humble perseverance.

In this way, the Philokalia continues to function as the core textual witness of Orthodox Hesychasm, not because it explains prayer intellectually, but because it teaches the soul how to return to God.

Saint Gregory Palamas and the Hesychast Controversy

Barlaam of Calabria and the Criticism of Hesychasm

By the fourteenth century, Hesychasm had been practiced quietly for hundreds of years within Orthodox monastic life, especially on Mount Athos. Inner prayer, watchfulness, and continual invocation of Christ’s name were already deeply established traditions. What changed during this period was not the practice itself, but the need to defend it publicly.

The controversy arose when a learned monk from southern Italy, Barlaam of Calabria, encountered Athonite Hesychasts and began criticizing their spiritual claims. Barlaam was highly trained in Western scholastic philosophy and approached theology primarily through intellectual reasoning. When he heard monks speak about inner stillness and experiential knowledge of God, he concluded that they were confused or deluded.

Barlaam argued that God could only be known intellectually and that any claim to direct spiritual experience crossed into superstition. He rejected the Hesychast understanding that prayer could lead to real communion with God, insisting instead that divine knowledge must remain purely conceptual. In his view, mystical prayer reduced God to emotional sensation or imagination.

This criticism struck at the heart of Orthodox spirituality.

If Barlaam were correct, then centuries of inner prayer were misguided. The lived experience of countless monks would be reduced to psychological illusion. Hesychasm would become merely devotional sentiment rather than genuine encounter with God.

The defense of Hesychasm was articulated most clearly by Gregory Palamas, an Athonite monk who later became Archbishop of Thessalonica. Palamas did not invent Hesychastic theology. He gave language to what generations of praying Christians had already experienced.

At the center of Palamas’ teaching was the distinction between God’s essence and God’s energies.

Orthodox theology affirms that God in His essence remains forever unknowable. No created mind can comprehend what God is in Himself. This protects divine transcendence and prevents God from being reduced to an object of human understanding. Palamas fully agreed with this ancient teaching.

However, Palamas also insisted on something equally essential: although God’s essence is inaccessible, God truly gives Himself through His divine energies.

These energies are not created effects or symbolic metaphors. They are God Himself in action. Through them, God reveals His presence, communicates grace, and draws humanity into communion. In other words, while God cannot be grasped intellectually in His essence, He can be genuinely encountered through grace.

This distinction preserved both mystery and intimacy.

God remains infinitely beyond human comprehension, yet He is not distant. He is actively present in the life of the believer. Prayer is therefore not merely reflection about God. It is participation in divine life.

Palamas explained that Hesychastic prayer does not manufacture spiritual experiences. It opens the heart to receive what God freely gives. Any peace, light, or inner stillness that arises is not produced by technique but received as gift. The monk does not generate grace. He becomes receptive to it.

This teaching also clarified the nature of salvation in Orthodox Christianity.

Salvation is not simply moral improvement or intellectual belief. It is participation in God’s life. Grace is not external assistance. It is real communion. Through prayer, repentance, and humility, the human person is gradually united to God’s energies and transformed from within.

This process is known in Orthodoxy as theosis, the gradual healing and divinization of the human person by grace.

The implications were profound. If Palamas was correct, then Hesychasm was not fringe mysticism but central to Christian anthropology. It revealed what humanity is created for: communion with God. Inner prayer was not psychological self-soothing but the means by which the heart becomes a dwelling place for divine presence.

A series of Church councils in Constantinople examined the controversy carefully throughout the 1340s and 1350s. After extended theological debate, Palamas’ teaching was affirmed, and Barlaam’s position was rejected. The councils formally recognized the essence-energies distinction and declared Hesychasm an authentic expression of Orthodox faith.

This affirmation did not elevate Hesychasm into an elite spirituality reserved for monks. Instead, it confirmed that experiential communion with God belongs to the very heart of Christianity. It established that prayer is not symbolic but participatory, and that grace is not imaginary but real.

Equally important, Palamas emphasized that Hesychasm must always be grounded in humility. Prayer without repentance becomes illusion. Inner stillness without obedience becomes pride. Spiritual experience pursued for its own sake becomes deception. True Hesychasm is inseparable from confession, sacramental life, and love for others.

The Church’s affirmation of Palamas ultimately preserved something essential.

It protected the truth that God desires to be known, not abstractly, but personally. It safeguarded the lived tradition of inner prayer. And it ensured that Orthodox Christianity would continue to understand salvation not merely as forgiveness, but as transformation through communion.

Through Saint Gregory Palamas, Hesychasm received its theological voice, but its heart remained unchanged. What had been discovered in desert solitude and preserved on Mount Athos was now articulated clearly for the entire Church: that through humility, prayer, and grace, the human heart can truly encounter God.

Church Councils and Dogmatic Affirmation

The Hesychast controversy did not end with the personal writings of Saint Gregory Palamas. Because the questions involved touched the very nature of God, grace, and salvation, the Church addressed them formally through a series of councils held in Constantinople during the middle of the fourteenth century. These gatherings were not minor disciplinary meetings. They were full theological examinations of whether Hesychasm represented authentic Orthodox Christianity or a dangerous spiritual deviation.

Between 1341 and 1351, multiple synods carefully evaluated the teachings of Barlaam of Calabria, his successors, and Gregory Palamas. The debates were rigorous and detailed, involving bishops, theologians, and monastic representatives. At stake was a fundamental question: can human beings truly experience God through prayer, or is divine knowledge limited to intellectual concepts alone?

The councils ultimately affirmed Palamas’ articulation of the distinction between God’s essence and God’s energies, declaring it fully consistent with Orthodox doctrine. They rejected Barlaam’s rationalistic approach and confirmed that while God’s essence remains forever unknowable, God truly communicates Himself through His uncreated energies. This meant that Hesychastic prayer was not psychological fantasy or emotional projection, but genuine participation in divine life made possible through grace.

This decision carried enormous spiritual weight.

By affirming Palamas, the Church formally recognized that inner prayer is not peripheral to Orthodox Christianity. It belongs to its core. The councils declared that experiential communion with God is not reserved for extraordinary mystics, nor confined to abstract theology. It is the natural fruit of repentance, humility, and faithful prayer within the life of the Church.

Equally important was what the councils did not affirm.

They did not promote emotionalism, spiritual experimentation, or the pursuit of mystical experiences. On the contrary, they reinforced the traditional Hesychastic emphasis on sobriety, discernment, and humility. Inner prayer was validated, but always within the sacramental and communal life of Orthodoxy. Spiritual experience was acknowledged, but never detached from repentance or obedience. Grace was affirmed as real participation, yet never treated as something a person could control or manipulate.

Through these councils, Hesychasm was established not as a fringe monastic spirituality, but as dogmatic Orthodox theology. The Church publicly declared that salvation involves real transformation through communion with God, and that this communion is accessed not merely through intellectual belief, but through lived prayer.

The affirmation also clarified the Orthodox understanding of grace. Grace was not defined as created assistance or symbolic favor. It was proclaimed as God’s own uncreated energy shared with humanity. This preserved both divine transcendence and divine intimacy, allowing Orthodoxy to maintain that God remains beyond comprehension while still being truly present in the heart of the believer.

In practical terms, the councils gave theological language to what monks and faithful Christians had already known through experience. They confirmed that the quiet work of inner prayer, practiced for centuries in deserts and monasteries, was not spiritual imagination but authentic encounter. The Church placed its authority behind the ancient wisdom of Hesychasm, ensuring its continuity for future generations.

This dogmatic affirmation also safeguarded humility as the foundation of spiritual life. The councils made clear that inner prayer cannot be separated from repentance, confession, and love. Any spirituality divorced from these becomes distortion. Hesychasm was upheld precisely because it produces not pride, but softness of heart, patience with weakness, and growing compassion for others.

Through this process, Orthodoxy preserved a delicate balance. God remains unknowable in essence, protecting divine mystery. God is truly experienced through energies, protecting real communion. Prayer becomes participation rather than abstraction. Salvation becomes healing rather than mere legal pardon.

The Church’s affirmation of Hesychasm therefore stands as one of the most important moments in Orthodox history. It confirmed that Christianity is not only something believed, but something lived inwardly. It declared that prayer is not symbolic, but transformative. And it ensured that the path first walked in desert solitude would continue to guide believers toward communion with God.

Modern Orthodox Hesychasts

Although Hesychasm is often associated with monks on Mount Athos or elders in remote monasteries, its living presence today extends far beyond monastic walls. Modern Orthodox Hesychasts are not confined to cloisters or deserts. They are found quietly throughout everyday life, practicing inward prayer while fully participating in the responsibilities of the world.

They are teachers standing in classrooms, nurses walking hospital corridors, parents preparing meals, tradespeople working with their hands, accountants balancing ledgers, and caregivers tending to the elderly. Their lives look ordinary on the surface. They attend Divine Liturgy, go to work, raise families, struggle with fatigue, and navigate the same pressures as everyone else. What distinguishes them is not outward appearance but interior orientation.

These men and women have discovered that the Jesus Prayer can accompany every moment.

Some begin their day with a few minutes of stillness before responsibilities take over. Others whisper the prayer while driving to work or waiting in line. Many carry it quietly through conversations, errands, and household tasks. Some return to it in moments of stress or discouragement. Others let it rise naturally during joy and gratitude. The form varies, but the intention remains the same: to live before God.

This quiet diffusion of Hesychasm into ordinary life reflects the original spirit of the tradition. Hesychasm was never meant to be a spiritual specialty reserved for a few exceptional souls. It emerged from the Church’s understanding that prayer belongs to every Christian, not just monastics. While monks may have more time for silence, laypeople bring prayer into workplaces, neighborhoods, and families. The setting changes, but the inner work remains identical.

What is especially striking about modern Hesychasm is how invisible it is.

There exists today a silent fellowship of prayer that has no formal membership, no public organization, and no outward sign. These believers are not connected through conferences or movements. They rarely speak about their inner practice. Most would never identify themselves as mystics. They simply pray.

This hiddenness is not accidental. Authentic Hesychasm produces humility rather than spiritual identity. Those who practice inward prayer do not seek recognition. They are often the least likely to speak about it. Their spiritual life unfolds privately between themselves and God, supported by confession, sacramental life, and quiet perseverance.

In Orthodox understanding, mysticism does not mean extraordinary experiences or dramatic spirituality. It means living relationship with God. True mystics are not marked by visions or emotional intensity, but by gentleness, patience, and compassion. They become slower to judge, quicker to forgive, and more aware of their own weakness. Their prayer does not make them superior. It makes them softer.

This is why Orthodox mysticism appears so ordinary.

It is woven into daily life rather than separated from it. It manifests in small acts of kindness, in restraint of angry words, in silent endurance of difficulty, and in repeated return to prayer when the mind wanders. The Hesychast path in the modern world looks less like dramatic spirituality and more like quiet faithfulness.

Parents learn to pray inwardly while caring for children. Nurses repeat the Jesus Prayer while tending patients. Tradespeople carry it through physical labor. Teachers return to it between lessons. None of this draws attention. Yet this is precisely how Hesychasm spreads, not through visibility, but through hearts quietly remembering God.

In this way, Hesychasm continues exactly as it always has.

It moves from person to person, not through programs but through lived example. It takes root wherever someone chooses to remain inwardly present to Christ. It flourishes in humility rather than performance. It grows through perseverance rather than intensity.

Modern Orthodox Hesychasts remind us that mystical life is not separate from ordinary life. It is ordinary life lived with interior awareness of God. The same prayer first practiced in desert caves now rises quietly in kitchens, classrooms, hospitals, and workplaces. The same inner stillness sought by ancient monks is now cultivated amid traffic, deadlines, and family responsibilities.

Hesychasm survives because it adapts without losing its essence.

It teaches that intimacy with God does not require withdrawal from the world. It requires attention within it.

And in that attention, countless ordinary believers are quietly becoming places where prayer never stops.

How to Begin Orthodox Hesychasm

Beginning Hesychasm does not require special knowledge, advanced techniques, or dramatic changes to your life. Orthodox inner prayer starts simply, with a willingness to become still and to return to Christ again and again. The tradition emphasizes small, faithful beginnings rather than ambitious spiritual goals.

A simple sitting prayer is often the easiest place to start. Find a quiet space where you can remain undisturbed for a few minutes. Sit upright in a relaxed but attentive posture. You do not need to force stillness into your body. Let your shoulders soften, your jaw relax, and your breathing settle naturally. Close your eyes if it helps reduce distraction, or keep them gently lowered.

Begin repeating the Jesus Prayer slowly and deliberately:

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

Say the words quietly or inwardly. Do not rush. Allow each phrase to land. At this stage, prayer is intentional and effortful. You are choosing to return to Christ with every repetition. This is normal and expected. Hesychasm does not begin with automatic prayer. It begins with conscious turning.

Distraction will appear almost immediately. Thoughts will wander. Images will surface. Memories will interrupt. This is not failure. It is simply the condition of the modern mind. Orthodox Hesychasm does not teach you to fight these thoughts aggressively or analyze them. Instead, when you notice distraction, you gently return to the prayer. No frustration. No self-criticism. Just a quiet reorientation toward Christ.

This repeated returning is itself the practice.

Each time you come back to the prayer, you are training attention. You are teaching the heart where to rest. Over time, this builds inner stability, but in the beginning it feels repetitive and sometimes discouraging. The Fathers are very clear that perseverance matters far more than immediate results.